Of the traditional styles of mowing movement that could rightly be referred to as “correct”,

there are many indeed. What qualifies them as such is that they accomplish the job expected

of them satisfactorily by a group of people, usually members of a certain regional culture.

Some of these styles outright defy the oft-repeated advice (of the most recent mowers’

generation): “Do NOT lift the blade off the ground between strokes”.(33)

However, what these various “correct” mowing styles have in common is that during the

actual cutting portion of the stroke the blade is aligned with the ground surface horizontally so

that the stubble ends up uniform throughout, regardless of the respective region’s traditional

width, which customarily ranged from 150 cm to 220 cm. It is this uniformity of cut stubble

that matters and determines the “correct” designation. Figure 41 is a representation of the

blade during the different positions of the forward (cutting) and return strokes. With slight

variations (e.g. the Alpine style mowing stroke using blade models with highly elevated

points) this illustration of the cutting/forward stroke could be said to more or less represent

the universal ‘close-to-the-ground’ technique shared by experienced mowers. The return

stroke as illustrated here represents the path that our blades follow, but (as pointed out in

Note 33) is quite different from some other styles.

Several years before having had the opportunity to observe some of the traditional mowing

variations, we (quite unintentionally) ‘invented’ a technique that seemed to make best use of

the body’s innate potential to propel this tool. After practicing it for a few seasons, we

introduced this somewhat radical mowing style to the new generation of mowers, initially in

North America, later in Europe and elsewhere.

(34)

What is “radical” about it? The primary difference is in the action of the legs. They are

employed in helping to propel the blade to a far greater degree than appears to have been

practiced anywhere in the scythe’s old homes that we are familiar with. By merely bending

and straightening them in turn, they affect the sideways body shift at each half of the complete (back and forth) stroke.

In this manner the arms (especially the right one) are spared some of the demands typically

required of them in most styles of mowing movement.

(33) There is, for instance, a region of Austria where the traditional (and obviously efficient) mowing style consists of precisely

that ‘forbidden’ touch; those old farmers have cut a LOT of grass by lifting the blade upwards of 30 cm each time between

strokes. We have also observed plenty of blade-lifting in Switzerland (though it is not necessarily the ‘Swiss standard) as well

as, to various degrees, elsewhere in Europe.

(34) Relatively inexperienced as we were at the time, an ‘introduction’ per se was not our intent, though observing in retrospect,

the technique appears to have become somewhat widely embraced. Now it is presented in many videos on YouTube – be they

from USA, UK, Australia, Czech Republic, etc. – and sometimes referred to as the ”ergonomic” or “Tai chi” mowing style. As to

the latter analogy, we wish that such misconstruing of the noble ancient concept of Tai Chi had nothing to do with us; the

variations presented are, more often than not, partial distortions, missing some essential ingredients that, from our

perspective of both theory and practice, bear little relation to the ‘flow’ and mental state striven for during the practice of the

“inner” styles of oriental martial arts, Tai Chi included.

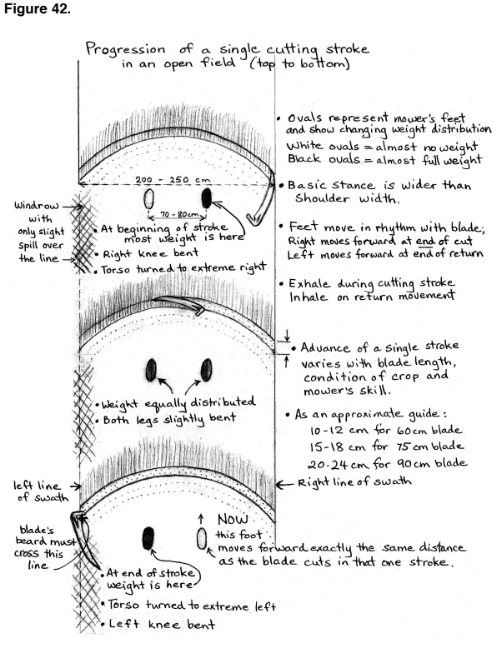

Before studying the illustration of this wide movement in Figure 42 we suggest the following

qualifications be considered:

• Although the majority of our mowing entails the use of this particular wide movement

we certainly do not intend to present it as a one-size-fits-all standard. Certain

variations of it – with swath width being the most significant of them, advance at each

stroke secondly – can still fall into (from our perspective) the desired category of

“cutting the most grass with the least energy expended” (with speed itself considered

less important).

• The wide movement as shown here is advantageous for cutting fodder to be made into

hay, mulch, or fed green, and for mowing lawns, not harvesting mature cereals.

• In this illustration the blade at the beginning of the cutting stroke is NOT drawn fully

extended. Depending on individual variations, in real life the stroke mostly begins with

the blade farther back, with the point about where the heel of the drawn blade is now.

More important, however, is the blade’s position where the cutting phase of the stroke

ends. There it should continue fully to the left (more or less as drawn) so that the grass

is cut cleanly all the way to the line defining the leftward side of the sward. Because it

is the portion of the edge along the blades’ beard that cuts the very last of the stems

within each stroke, the beard itself must cross that line. At that moment most of the

blade’s length has already moved past it, but because the length of the snath limits its

movement further leftward, it is pointing back behind the mower.

Breathing deeply in synchrony with one’s strokes has, for the most part, been left out of

instructional guidelines of many who now advocate this wide movement, and a correction in

this regard would be nice. Still, on the whole, the style does seem to appeal to many novices,

including not only the physically fit and flexible; provided they become adequately competent

in edge maintenance, many elderly men and women often find it surprisingly undemanding

and satisfying to practice. We have also witnessed a few attentive 10 year olds picking up

this technique almost instantly. In these cases they were provided with adequate hands-on

guidance, an easy-to-cut stand of grass on smooth and relatively level terrain, and a well-

fitted scythe with a suitably sharp blade. At least two of those children were performing this

extra wide stroke so flawlessly within 15 minutes that a seasoned mower watching them

might think they had been practicing it for years. Based on such experiences, we are

convinced that the transition from this wide movement to a narrow one is easier than the

other way around.

It is true that a narrow stroke is more forgiving, in that shortcomings with regard to the

blade’s adjustment, sharpness, and how exactly it is guided can be more easily ignored.

Thus poorly adjusted scythes can be used without it being obvious that they would indeed

benefit by fine-tuning. The downside is that various ‘bad’ habits are often picked up as a

consequence. Applying too much force is one of them, possibly the worst, because it can be

destructive to the tool and exhausting to the user. It is partially for this reason that we

advocate the initial practice sessions to be ones where flaws are more readily noticed, and

corrected before they become ingrained.

Technique diversity

While mowing along roadsides and fences, amidst closely spaced trees, around buildings,

boulders or other obstacles, and over uneven terrain, there are countless variations of how

the blade can be guided with regard to the stroke pattern, its slice/chop ratio, as well as the

pressure with which the blade is pressed towards the ground surface. For instance,

whenever conditions do not allow for a fully extended stroke, the sward’s width can be

reduced and is often accompanied by narrowing one’s stance. If after a few narrower strokes

there is again space for a wider swath, one can easily take advantage of the space and just

as quickly switch back to wide strokes. In a tangled or extremely dense stand both the

swath’s width and the forward advance at a stroke should generally be reduced.

Unexpectedly coming upon an area of excessively uneven surface, or one strewn with small

rocks, the mower can temporarily but effectively alter the blade’s lay (i.e. lift the edge off the

ground) by bending their left arm a little more to raise the upper end of the snath and/or ease

off on its pressure against the surface (even though its cutting efficiency will thereby be

temporarily lessened). Having first learned the basics well, such modifications can be

performed in a deliberate and graceful manner; with sufficient practice, these adjustments in

technique become nearly instinctive.

Regretfully, in the majority of demos, live (during scythe courses) and in videos, the scythe is

presented in what we perceive to be an imagination-limited manner in relation to how flexible

and multi-tasking a tool it really can be. Greater diversity in mowing conditions would go a

long way towards painting a more realistic picture of the potential creativity that can be given

freer rein while using this wonderful tool.

It would therefore be far more educational if scythe courses took place on terrains that offer

much more variety than a flat meadow or a lawn. Areas which include large embedded rocks,

fence lines and patches of cane fruit would better prepare the students for the sort of

challenges many of them face while trying to mow the neglected, overgrown and often rough

terrain on their diversified small holdings or recently purchased country properties. Novices

sometimes take remarkably long (in many cases years) to figure out on their own some very

basic trimming strokes and ways to apply them. Some attempts have been made in the

aforementioned books by way of drawings and photos, though they are limited in scope in

relation to all that actually happens out in the field.

What, for instance, is typically demonstrated as the “correct” approach for trimming orchards

is the one in which the mower walks around trees in a complete circle while making a semi

wide swath with the windrow accumulating either towards or (more safely for novices) the

width of a stroke away from the tree. Yes, that is a good beginners’ technique but one that

cannot be effectively used if there isn’t space enough for the width of the stroke, or complete

access for a person to do the ‘walkabout’. With some of the techniques we discuss below,

trees or fence posts with wire attached to them can be cut around while remaining practically

in one place (on one side of the fence).

There are indeed many ‘everyday’ trimming techniques that are universally used throughout

Europe. The old mowers do not necessarily think of them as “trimming” versus “field”

oriented. They are all just various scythe strokes used whenever appropriate, and none of

them appear to have formal names; within an old scythe culture it was not needed. But

discussing the topic among people miles (and continents) apart, mostly by written word,

presents a challenge the old mowers didn’t have. Certain commonly understood terms would

be helpful. (That was the reason that, 20 years ago, while trying to call attention to the

benefits of having distinctly-sized snaths for different purposes, we added the two hitherto

non-existent terms “trimming” and “field” mowing to new scythe users’ lexicon.)

Now, attempting to present a couple of trimming techniques that are uncommon, but for

which we find frequent use, is somewhat awkward without a descriptive name. One of them,

here on the homestead, we refer to as the “zigzag” and the other simply as “backstroke”.

Well, “zigzag” leaves a lot to the imagination, and “backstroke” is also not descriptive enough

nor accurate in view of the regular mowing movement’s forward and backward strokes

discussed here and elsewhere. (35)

The ‘zigzag’ appears to have been another one of our “accidental” inventions. In certain

situations it can be very helpful; it may not even be much of a stretch to say that it can

sometimes “save the day”. It consists of short back-and-forth movements of the blade that

can be more accurately controlled than those of any other mowing technique. It is thereby the

most suitable one for situations where a little misjudgment or slip would cut off someone’s

precious ornamental flower, injure the bark of a young fruit tree or, conversely, damage a

section of a meticulously prepared edge (no, not lawn edging; the blades’ edge). However,

for this technique to function as intended, the blade should be pressed still more tightly

against the ground surface than we recommend for the wide field stroke in difficult mowing

conditions (see Chapter 8). For that reason alone, using it frequently could help people

appreciate the merit of very close contact with the ground surface also in other situations,

including those where long blades and the wide movement can be indulged in.

We consider the ‘zigzag’ difficult to beat while trimming under low hanging fences, around anthills, in

amongst boulders and between very closely spaced small fruit plantings or similar

situations where the utmost control of the blade’s action is called for. Applying it also makes

possible the cleaning up of trampled spots or clumps of certain grasses that sometimes resist

other common trimming techniques.

(35) What we think of while referring to the ‘backstroke’ is more along the lines of ‘The Slovakian Backwards Stroke’ because it

was in Slovakia where an old mower first showed it to Peter many years ago, and he had not before or afterwards seen it used

in other lands to which he traveled. But then in 2015 when Spanish-born Alfonso Diaz visited us for a snath-making

workshop, lo and behold, he was using the same technique in order to sometimes clean up (on the return stroke) a sliver of

grass that his forward stroke may have missed. His father apparently used it that way. So much for it being “the Slovakian

original”! When Niels Johannsen was here in 2006 we showed him the backstroke, which he subsequently took to a level that

would likely spin the heads of mowers who used it elsewhere in some form or another. At that time he also introduced us tohis “Danish original” which has the edge of the blade aimed upwards (perpendicular to the ground surface) for very niche-

specific purposes. Other than suggesting the watching of Niels’ videos, we shall leave it off the table here because if the safety-

conscious folks saw us actually using it (with the blade sometimes moving very close to our bare feet) they might report us tothe appropriate authorities for spreading “dangerous” ideas… 🙂

Some characteristics of the ‘zigzag’ mowing stroke: The blade’s movements are from about

20 to 40 cm long. In its basic form only the stroke to the left does the cutting, and usually

does not return as far to the right as it started from. With other words, it takes short ‘runs’ at

its target, backing up just enough each time to gather new momentum and prevent (or greatly

reduce) any chances of getting ‘stuck’. Over such short distances the blade’s speed does not

need to equal the more regular mowing stroke, hence its increased control and accuracy.

That, plus close contact with the ground surface, acts as a breaking system if required.

(Especially while trimming in ‘touchy’ places, the blade kept hugging the ground surface is

less likely to slip past the spot it is intended to stop in order to prevent a mishap – like cutting

into a fruit sapling one is mowing around.)

The advance of the ‘zigzag’ at a stroke is not necessarily a ‘forward’ one as we think of it

while performing most of the common mowing patterns. It may be more directly sideways,

making a ‘swath’ only 10-30cm wide (usually while mowing under a fence) or (if the obstacle

course to be mown around requires it) it can proceed at various ‘diagonal’ directions,

combining both a forward and sideways advance.

In some situations the zigzag technique can be enhanced by combining it, briefly, with a

normal forward stroke or, for the purpose of shorter cuts, with the one that cuts ‘on the return

stroke’ (mentioned in Note 35). The latter slices during the phase when the blade is moving

to the right (with its beard leading). This (combination) would then be one of the “non-basic”

forms of the zigzag technique. Yet to even semi-accurately describe the resulting

combination of the two may well be beyond our ability, so we won’t even try…

The stroke which does the cutting when a right-handed blade is moving towards the right

needs to be simultaneously moving not only to the right but also slightly ‘inward’ (towards the

mower’s feet). It is not used for the purpose of mowing an area per se, but mostly as a one-

time-only stroke to perhaps clean up (on a return stroke) some grass that was missed during

the normal cutting stroke. This technique (as opposed to the ‘zigzag’) is not dependent on

any ground contact, and can be applied to a range from very low targets to those above

one’s head. Thus it is invaluable in any ‘jungle’ of vegetation, particular patches of old berry

bushes where stems of different ages (and toughness!) present themselves on numerous

angles, and there is not much space for the blade’s common back-and-forth movement.

Much as in the case of the ‘zigzag’, the control of the tool it allows (regarding any left/right

miscalculations) is greater than with the common trimming strokes.

“The Path of Least Resistance”, in brief

Not often is a stand of vegetation, be it a small patch or a large field, equally easy to cut from

all directions. The relative ease is determined primarily by the lean of the stems and

secondarily by topography (i.e. uphill/downhill, sideways slope etc.). Sometimes the

differences are insignificant and can be ignored. However, even then, we highly recommend

paying attention to the small variations in the blade’s performance as mowing proceeds

either slightly uphill or downhill, or if a patch of grass contains the subtle trail of a fox, a more

trampled overnight bed of a deer, or is thoroughly flattened by the latest storm. As is the case

with most creative endeavors, the nuances of all this are really difficult to communicate in

words on a written page. A person, again, simply needs to get out there and play with both

the (vague) theory and (educating) practice of it.

A few general hints:

a) Vegetation is more easily cut when it leans either away from, or to the right of the mower.

There are differences between these two; sometimes significant and other times not so. For

instance, if the stand has been leaning forward (away from the approaching blade) for a

certain period of time, and especially if it contains some creeping plant species (various

vetches, Virginia Creeper, etc.) it will have created what may be described as an interwoven

mat. This mat (as opposed to old, dead thatch underneath new growth) is not so difficult to

cut off at the base, but is sometimes quite troublesome to disconnect so as to allow the cut-

off vegetation to be moved over to the windrow in the expected one-stroke portions. Making

2-4 strokes in sequence, but without insisting that they clear the view of the surface, and then

hooking onto a piece of that ‘mat’ with the blade, as a separate movement, and dragging it

over to the left (or in a heap where the windrow usually is) may at times be the best, or even

the only sensible approach. Alternatively, if instead such a stand can be approached (at

times it can’t) so that it leans to the right, disconnecting each stroke would likely be easier.

b) Vegetation is more difficult to cut if it leans towards, or to the left of, the mower.

Here (as in ‘a’) the degree of difficulty (and/or ease) in these two variations depends, beside

a few other factors, on the degree of the lean. If the lean is only slight it may be somewhat

insignificant, and occasionally even advantageous. For instance, if a tall stand is leaning

slightly leftwards it may fall into the windrow easier than if it were completely upright, without

making the cutting itself more challenging. Beyond a certain degree, however, the lean can

become a nuisance. Often what could easily be cut if leaning on the same angle to the right

is practically impossible to cut when it is leaning to the left. This is true also for leans towards

the mower.

On the other hand, nearly all untangled leans away from the mower are far easier to deal

with, and if approached correctly can be cut even if the grass is lying so low as if it had been

recently run over by a roller.

c) It is easier on one’s back to mow uphill, rather than downhill. However, if the vegetation is

fairly mature, it will probably be leaning downhill to various degrees, and starting from the top

and then mowing downhill may be either helpful or outright necessary. As discussed in

Chapters 3 and 11, in such cases it helps if the snath used for that purpose is longer

between the lower grip and the blade than ‘normal’.

Another option to consider on extended slopes is to move diagonally. The mowers of very

steep mountain meadows often employed the given advantages or disadvantages of either,

and did not follow a certain approach ‘religiously’. They knew that if one proceeds from the

bottom upwards but also diagonally to the left, the grass will probably be more difficult to cut

but the cut material will more easily flow into the windrow. Moving diagonally to the right will

make the cutting itself easier, but the weight of the cut material has to be pushed against

gravity into the windrow. While the latter approach is always possible, the former (depending

on the degree of vegetation’s lean) is not.

The hints communicated above represent only an outline of the various factors to consider.

And considered they ought to be, if something of a “path of least resistance” is to be found.

That path is always there!

Harvesting Grains

This topic really merits a much more comprehensive coverage than we give it here. However,

it is addressed briefly because so many aspiring scythe users of the present (chiefly

Western) generation have expressed a desire to harvest the grains for their daily bread with

the same tool as they intend to cut their lawn or meadows. They deserve to be cautioned that

cutting small grains and other annuals for purposes of edible cereal harvest presents

additional challenges regarding how the blade needs to be guided in its path; prior

experience in using the scythe for general “grass” cutting is recommended. Also, the two

diagrams presented so far in this chapter do not very well apply to the harvesting of cereal

crops. In addition, an accessory called a “grain cradle” is highly useful to help orient the

heads of the stalks in one direction as they are being cut off – something considered crucial if

the “sheaves” into which the cut grain is subsequently tied are to be cured in standing

formations generally known as “stooks”. (We would like to point out that, on a small scale,

there are other approaches to handling grains after they are cut than tying them in sheaves

and curing in stooks, but that’s a topic for another day…)

Cradles have been made in a wide array of designs. The simplest of them consists of merely

two pieces of string and a small, freshly cut green sapling, which can literally be made right

out in the field. At the other end of the spectrum are the versions used in North America

during the pre-industrial era – a difficult to self-make and relatively heavy contraption with

multiple steam-bent curved ‘fingers’, sometimes the length of the blade and extending above

it. Regarding the complexity of design, the majority of cradles fall between these two

extremes. A sizable book could indeed be written on the topic of grain cradles with details of

their construction and use…

Because cradles are not readily available to most scythe users who perceive a need for one

on their own homesteads, we suggest considering a serrated sickle as an alternative, at least

initially. Thousands of hectares of grain had in the past been harvested by farmers in Europe

and throughout Asia with sickles, and in many “underdeveloped” countries that is still the

case, with India being a prime example. For small home kitchen sized plots a sickle is quite

sufficient, and operating one does not present the challenge of learning to make, adjust, and

then operate the cradle, especially if the crop to be harvested is not standing ‘perfectly’

upright with no broken stalks and tangled heads. That said, we perhaps ought to be more

encouraging regarding the combination of scythes and grain harvesting. After some

experimentation with the simple string and sapling grain cradles, we conclude that this very

basic design can indeed function satisfactorily. However, it requires due attention (and

repeated experimenting) while learning how to adjust it appropriately in a customized manner

for varying crop conditions. Some helpful hints on cereal cutting have, as of the past few

years, been presented on the Internet. Here are a few more:

• The width of an individual cutting stoke should be narrower and the pattern less

circular than when cutting grass.

• The advance at a stroke can be greater. Exactly how much greater will depend on the

particular grain crop, the terrain, the length of blade used, and the condition of the

edge. In any case, blades with a more open hafting angle, which may not be well

suited for some green grass cutting, may function very well for purposes of grain

harvest.

• Because cereals usually do not need to be (and/or are not) cut as low to the ground as

is typical while harvesting green forages, the lay of the blade can be aimed further

upwards. That is, if the same snath/blade combination found to work satisfactorily

while cutting lawns or hayfields were to be used for a cereal harvest, a wedge can be

inserted under the tang (in order to lift the edge slightly away from the ground surface);

doing so may decrease the amount of force needed to make each stroke, and may

also cause less shattering of the grain heads.

• The actual cutting of most grain stalks (flax being one of the exceptions) is less

demanding of a keen edge than a dense stand of grass. Also, because the stalks are

generally relatively dry, they are easier to ‘bite into’ if the blade’s edge is somewhat

serrated than if smooth. For that reason, using a coarser whetstone for the periodic

touch-ups in the field is advisable; it does not matter whether the stone is natural or

synthetic (though, of course, coarse versions of the latter are now far easier to find).

However, the blade should still be sharp; if it is not, in areas with loose soils where the

plants are not so strongly embedded some of them may get pulled out of the ground

with their roots, instead of being cut.

• Another issue to consider is the nature of the ground surface. As opposed to an

established sod, which often offers a ‘carpet’ of edge protection for the mower and

his/her tool, the relatively loose surface under annuals rarely provides such conditions.

The challenge is increased in naturally stony/rocky regions and while the terrain’s

caretakers may have taken the time to free the surface of loose or slightly embedded

‘edge obstacles’ from the surface of old hayfields, doing so to the same extent with

grain fields is less likely. For that reason the edge of the blade can or should aim

possibly still further away from the ground than already mentioned above. Exactly how

much further it can be so the blade cuts efficiently yet is positioned maximum distance

away from the rocks, needs to be determined on the spot in the field. At least 2-3

wedges of different thickness can be carried to the field and tried in turn to alter the

blade’s Lay (following guidelines on this theme in Chapter 5).

The illustration on the following page was drawn by Alexander Vido (of Scytheworks) for the

purposes of an instructional booklet produced for small farmers in India, and is based on his

experiences with wheat and rice harvesting in India and (wheat only) in Nepal. Because he

recently spent more time on this theme than anyone else we presently know of, and

designed the very cradle that is being successfully used (and reproduced in significant

numbers) in India, he (along with others similarly experienced) really are the ones to put

together a more complete feature on the topic – to be presented in Part 2.